For most of us, when we make major career choices, we tend to lean into what we’re good at. According to new findings from the University of California San Diego’s Rady School of Management, such skills may develop early in childhood and there can be significant differences depending on gender.

Researchers have long observed that fewer women than men study and work in the fields of science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). Now, it appears that women may self-select out of these fields partly as a result of receiving more early-childhood reinforcement in language arts, according to a new paper to be published in the journal American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings.

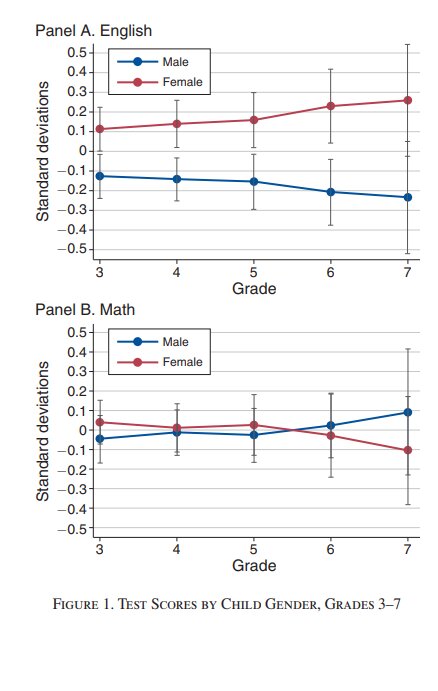

“We find girls are better in English than boys in grades three through seven,” said Anya Samek, an associate professor of economics at the Rady School and one of the study’s co-authors. “Because girls are more likely to do well in language fields early in life, they may find themselves more inclined to choose them for majors and careers. Thus, women may be underrepresented in STEM in part because of their cultivated talents achieved earlier in life.”

The findings are based on a longitudinal study in which the researchers examined time parents spend with their children from ages three to five alongside the children’s test scores when they were ages eight to 14.

The researchers also find more time parents spent teaching to children from ages three to five (up to three hours or more a week) correlated with better test scores when the children are ages eight to 14. For instance, teaching three or more hours predicted 6 percent higher scores in English for children in fourth grade, relative to teaching one hour or less.

However, there’s a gender gap in parental investment in the children from ages three to five. On average, parents spent more time with girls and several factors could contribute to this disparity. For example, compared to boys, the researchers found girls had a stronger ability to sit still and focus and parents of girls were also 18 percent more likely to report that their child liked it when they taught.

The study participants are mostly from Chicago and include 2,185 children and 953 parents who responded to surveys, 702 of whom also provided test-score data.

Girls did substantially better in language-related studies than boys, while scores for girls and boys in mathematics were more similar. They found a stronger correlation between parental investment with language scores than they did with math.

“I think it’s surprising to see that parental investments are correlated with the test scores in English but not in math,” said Samek. “It could be because we’re told to read to our kids at least 10 minutes a day. We’re told to introduce them to books and I think we probably spend less time thinking about how to engage children in math.”

Samek added, “We show that early-life investments by parents are strongly associated with later-life language skills but only weakly associated with later life math skills. It could be that parents just do not spend as much time teaching children math as they do reading. If that is the case, the next step may be to encourage parents to teach their young children math alongside reading.”

More information: Amanda Chuan et al, Parental Investments in Early Childhood and the Gender Gap in Math and Literacy, AEA Papers and Proceedings (2022). DOI: 10.1257/pandp.20221036

Citation: Girls excel in language arts early, which may explain the STEM gender gap in adults (2022, April 19) retrieved 19 April 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-04-girls-excel-language-arts-early.html

Did they control for socio-cultural factors? Because if not their conclusions are bunk.

- Female In-Class Participation and Performance Increase with More Female Peers and/or a Female Instructor in Life Sciences Courses

- Academic performance and single-sex schooling: Evidence from a natural experiment in Switzerland

- PDF - Ajai, J.T. & Imoko, I.I. (2015). Gender differences in mathematics achievement and retention scores: A case of problem-based learning method. International Journal of Research in Education and Science (IJRES), 1(1), 45- 50.

- PDF - Group Work in the Science Classroom: How Gender Composition May Affect Individual Performance

- Gender Gap in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM): Current Knowledge, Implications for Practice, Policy, and Future Directions

In an attempt to explain the link between gender and cognitive performance, research has examined the potential contributions of biology and environment. Although studies have examined whether biological factors such as testosterone exposure and greater brain lateralization are linked to superior mathematical reasoning and reduced verbal ability among males, findings have been inconclusive (Miller and Halpern 2014; Valla and Ceci 2011). Contrasting this are the more consistent findings of the sociocultural impact on gender differences in quantitative and verbal reasoning. Enriched STEM-related learning experiences predict notable STEM accomplishments even among mathematically gifted individuals (Wai et al. 2010). Additionally, parents may shape children’s math expectancies and performance by communicating their own gender-biased beliefs about how girls and boys should perform in math. For example, research has found that parents with stronger gender-math stereotype beliefs (e.g., beliefs that boys are better at math than girls and find math more useful and more important than girls) had higher perceptions of math ability for their sons and lower perceptions of math ability for their daughters. These parental beliefs, in turn, were positively associated with children’s own math ability beliefs (Jacobs and Eccles 1992; Tiedemann 2000a; b).

In addition, several cross-national studies indicate that greater cultural inequities between males and females are associated with larger gaps in mathematical performance favoring males (Else-Quest et al. 2010). Specifically, nations with higher proportions of women enrolled in postsecondary science courses and employed in science careers are less likely to explicitly endorse the stereotype that science is a masculine profession (Miller et al. 2015). These cultural values and beliefs about male/female abilities and roles are communicated to children through prominent adult figures. For example, a meta-analysis found that parental gender stereotypes reflecting male/female roles, interests, and abilities were linked to children’s gender schemas about others and their attitudes about gender occupational roles (Tenenbaum and Leaper 2002). Similar to the sex differences in math performance favoring boys, sex differences in verbal performance favoring girls may be partially derived from parental socialization at young ages. For example, research found that mothers talked more and used more supportive speech with their daughters than their sons (Leaper et al. 1998). In another study using nationally representative data, parents spent more time teaching girls verbal activities, such as reading and storytelling (Baker and Milligan 2013): some of these differences emerged in early childhood and persisted into elementary school. Although these studies did not link these socialization differences directly to cognitive performance, these differential experiences for boys and girls may partially explain why girls are more likely to outperform boys on standardized tests of verbal ability. Therefore, while biological factors cannot be definitively dismissed, sociocultural influences appear more likely to impact gender differences in cognitive ability.

This seems very speculative. It’s not like pursuing most STEM degrees doesn’t take a large amount of reading.

I didnt think so, I study molecular bio and aside from nursing programs, males are predominantly involved in the research. I see the article as a reasonable explanation for the why behind the what personally.

I didn’t need a scientific research to notice that all girls on my Spanish and English classes achieved better marks than boys, and that girls performed better on after-school English classes. But I guess, I’m happy now to know it is not a coincidence.

Having noticed systemic issues in education systems since my very first contact with them as a child, I would not be surprised if flaws in how education is performed are ultimately responsible for the differences rather than biology.

I would not be surprised if flaws in how education is performed are ultimately responsible for the differences rather than biology.

How do you explain that almost every society/culture on Earth more or less flaw’ed in the same way? It’s either a gigantic coincidence or there are biological root causes behind it.

Removed by mod

I wish there was some way to actually test this things. It is impractical to make a research that lasts for decades, starting from childhood until 25 or something.

There are well known research in gender studies / psychology about for example the cliché that girls are less good for math than boys which is of course complete bullshit.

You don’t need to wait 25 years to study that.

Speaking of systemic teaching issues, the only thing worse than math is physics.

I was able to do calculus at 10 yrs old (the reason I know that is kind of a long story), yet even at 20 years old I struggled to understand how it was taught.

Physics is worse because everything is always taught as an aprocryphal story about who discovered it and how. And then hand-waved away with math whenever questions arise.

Physics is tough, even crazier is the fact physics is labeled as the simplest science. This is due to physics only interpreting length, mass, time, and electric current. This claim is very misleading in my mind. Calculus was developed as a necessity to interpreted these four qualities to help better understand the world around us. But I couldn’t agree more regarding physics needing a full makeover to make the subject more approachable for sure.

I came here to say this and i downvoted the article, not because the actual findings are wrong, but the interpretation is fucked up. “we tend to lean into what we’re good at” i don’t think is true

it’s not that girl brains are hard wired for specific tasks, but:

- as the study points out, the teaching relationship is very different between boys and girls (girls are expected to behave and be studious, and will conform to that if they want to please)

- STEM circles have become heavily male-oriented: in the past IT jobs such as programmer were marketed to stay-at-home moms but since the 70s/80s and the rise of private commercial IT (micro-computers and the video game industry) the image has changed

This looks a lot more like a gender stereotyping/puberty effect?

Jesse what the fuck are ya’ll talking about? Mother fuckers don’t even acknowledge the patriarchy

Mother fuckers don’t even acknowledge the patriarchy

Why should they? They are scientists, not social media clowns.

^ Case in point, this is why women don’t want to be around STEM bros.

Nothing wrong with STEM bros. STEM folks are some of the nicest people on this planet.

Because my experiences are lesser than yours, of course. And as a woman I should bow to your superior knowledge.

By the same logic, why are your experiences superiour to mine?

They aren’t. But being privileged has a way of making people blissfully unaware of the way they harm others. Plus I have linked stats is other comments here supporting the claim that women struggle to perform in co-ed groups despite having similar cognitive ability. Fortifying this with my personal experience: I’ve seen how the stats play out in person. Men treat women like garbage while being totally blind to the fact that they’re being assholes.

But being privileged

You assume this based on what?

The only clown here is you and your apparent inability to observe the world around you. That and all the STEM idiots who think economics, STEM, and politics are somehow not related. What a fucking joke you are.

why so angry?

I don’t take kindly to idiots

I recommend a nice cup of tea to calm the nerves.

Now you’re just antagonizing me

Not sure what that means.